The American Zonophone Discography II: The Roots and Early History of American Zonophone Records 1898–1905

American Zonophone records have their roots in Frank Seaman’s National Gramophone Company, the exclusive sales agent for Emile Berliner’s Gramophone products. By the late 1890s, Seaman was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with Berliner’s commissions and pricing structure, as well as the company’s inability to make timely deliveries, produce a workable coin-operated disc phonograph, and develop overseas markets. In 1897 he opened a recording studio in New York, with the knowledge and consent of the Berliner company, ostensibly to demonstrate the recording process to the public. No masters from Seaman’s studio are known to have found their way into commercial production.

On October 1, 1897, Seaman resigned as president of National Gramophone and was replaced by Orville La Dow. Following Seaman’s departure, National Gramophone’s already strained relations with the Berliner company were largely severed. In December 1897, National Gramophone advertised a competing disc machine, the Vo-Co-Phone,1 for export to Europe. In the same month, Seaman reportedly hired former Edison engineer Theo A. Wangamann to undertake some experimental recording. It was reported that Rhinebeck & Sons (New York) plated and processed the masters, but as with the earlier demonstration recordings, no evidence has been found that any of these were produced or marketed commercially.

Seaman and La Dow launched the Universal Talking Machine Company on January 26, 1898.2 The company was organized to “manufacture, buy, own and sell, coin actuating and other automatic devices, and also machines for reproducing musical and other sounds…,” according to its incorporation papers. La Dow was elected president of the new company, while retaining his position as secretary and manager of National Gramophone, which would act as Universal Talking Machine’s sales agent. Seaman justified creation of the new company based on a clause in his 1896 contract with Berliner that allowed him to obtain machines and records from other sources should Berliner fail to deliver satisfactory goods in a timely manner, as was the case.

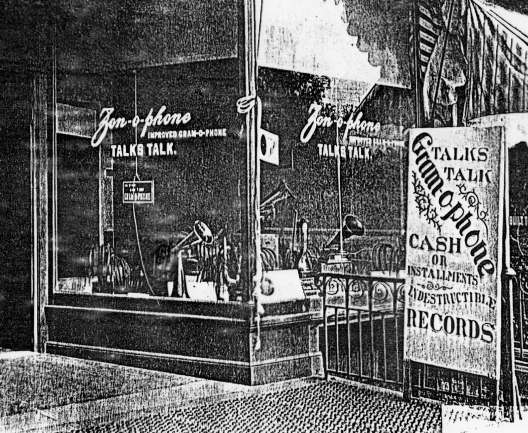

Initially, the Universal Talking Machine Company sold slightly modified Berliner products through National Gramophone. During the summer of 1898, Seaman hired H. H. Eldred to deliver a batch of Berliner machines to Europe from which the Berliner decals were effaced and covered with celluloid Zonophone nameplates. By the late summer of 1898, inventor Louis P. Valiquet had joined the Universal staff, and the company began manufacturing its own Zonophone machines (advertised as “improved Gramophones”), designed by Valiquet. Among his “improvements” was an additional peg on the turntable, adjacent to the spindle, to prevent slippage of the disc. Since Universal was still obtaining pressings from Berliner, and was not yet producing its own discs, it simply drilled an additional hole through the label area of the Berliner discs to accommodate the peg.

Universal claimed use of its Zonophone brand (unhyphenated in the original trademark application) on phonographs beginning August 11, 1898, although National Gramophone had already used the name as early as February 24, 1898, in a New York Evening Post advertisement. The Universal Talking Machine Company name first appeared in an advertisement in October of that year, in Munsey’s Magazine.

In the meantime, the American Graphophone Company (Columbia) was preparing to take legal action against National Gramophone (which was still handling the Berliner Gramophone), claiming that the Berliner reproducer infringed its floating-stylus patent. The case went to court in October 1898, and in November, New York Circuit Judge Lacombe ruled against National Gramophone. A restraining order, temporarily halting Gramophones sales in the United States, went into effect on January 25, 1899. The order was lifted in March, but by then, Seaman had decided to scuttle the National Gramophone Company.

appropriated Berliner’s “Talks Talk” slogan.

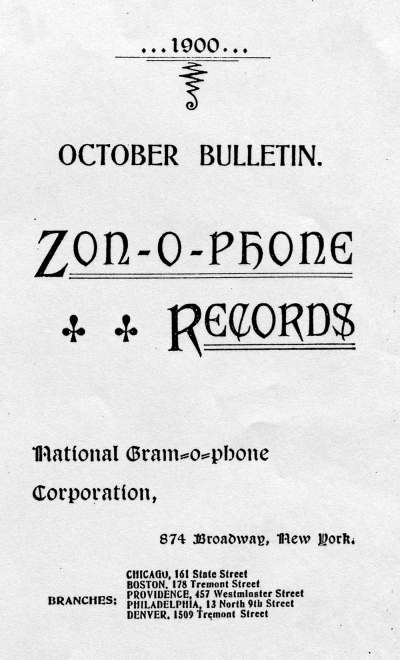

On March 10, 1899, La Dow joined Seaman to launch the National Gramophone Corporation, which would serve as sales agent for the Universal Talking Machine Company. The National Gramophone Company was dissolved on June 12, 1899. It has been reported anecdotally that Berliner suspended shipment of discs to Seaman at that time; however, Berliner discs recorded as late as November 1899 (which would have been issued no earlier than January 1900) have been found that were drilled for Zonophone machines. For a time, the National Gramophone Corporation accepted used Berliner machines and discs in partial exchange for new Zonophone products. The offer was withdrawn on December 10, 1900, with the company admitting, “We simply could not anticipate that we should be so completely overwhelmed with exchange orders.”3

Whether these late Berliner pressings were actually drilled and marketed by National Gramophone, or by third parties, remains a mystery. In the meantime, Universal had begun selling what it claimed were its own discs, but which in fact were pirated copies of Berliner recordings. Their dull appearance, somewhat degraded sound quality, and surface imperfections that don’t appear on genuine Berliner pressings all suggest that the stampers were electroplated from commercial Berliner pressings. The Gramophone brand and other tell-tale details were burnished out of the label area, leaving only the titles and original Berliner catalog numbers visible, in the original typeface. A catalog of these pirated recordings, if one was ever produced, has not been located, and thus far there has been no systematic attempt on the part of collectors and discographers to catalog the discs.

Large-scale production of Zonophone machines was under way by late 1899. The Phonoscope for June 1899 (which probably was published several months after its stated cover date) reported that the Universal Talking Machine Company had “started a large factory...where they employ about forty people, making Gramophones under the name of Zonophones, thereby avoiding the heavy royalties which the National Gramophone Corporation are obliged to pay to Emil Berliner, the inventor, and the Berliner Company.”

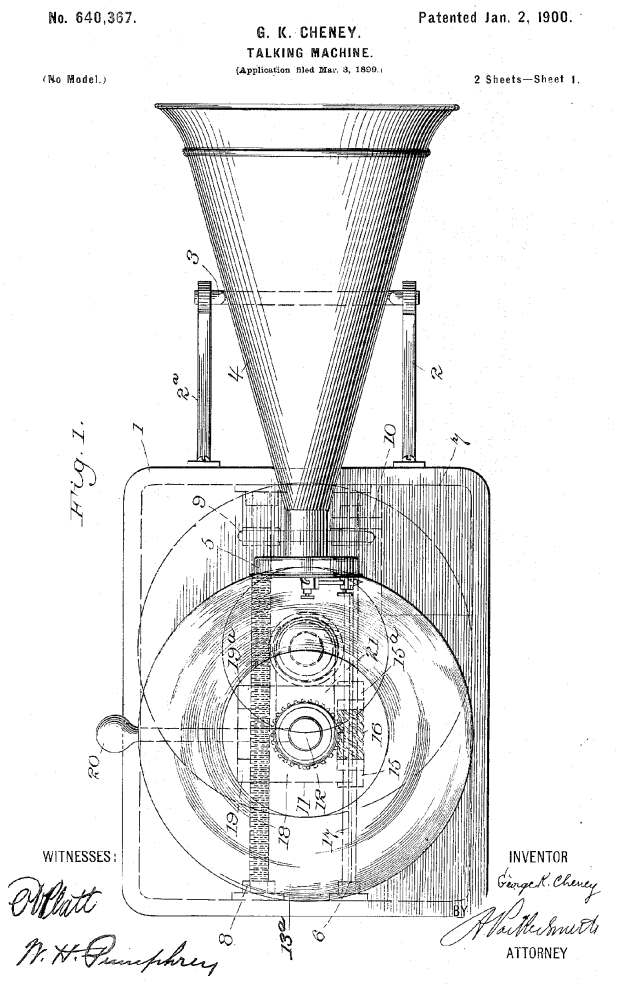

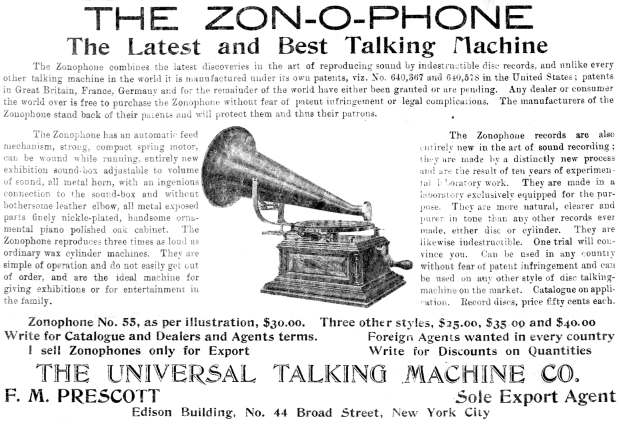

In November 1899, an unusual “auto-drive” Zonophone machine was advertised in The Phonoscope. It embodied George K. Cheney’s patents on a feedscrew-driven tonearm (#640,367)4 and an articulated horn mount (#641,578),5 which apparently were believed to afford the company some protection against Columbia or Berliner patent-infringement claims. The ad claimed,

The Zonophone combines the latest discoveries in the art of reproducing sound by indestructible disc records, and unlike every other talking machine in the world it is manufactured under its own patents, viz. No. 640,367 and 640,978 in the United States; patents in Great Britain, France, Germany and for the remainder of the world have either been granted or are pending. Any dealer or consumer the world over is free to purchase the Zonophone without fear of patent infringement or legal complications.6

A photograph of the feed-screw machine appeared in the ad, showing the same mechanisms pictured in Cheney’s patent filings, but it is uncertain whether it ever went into commercial production.

The Universal Talking Machine Company’s earliest original masters probably were made during the autumn of 1899, after the company entered into an exclusive arrangement with recording engineer John C. English. The contract was signed on June 12, 1899, although English’s formal date of employment was given in later court records as October 12. The contract specified that English would develop recording equipment and processes exclusively for the Universal Talking Machine Company and would assign all inventions and improvements to the company. The Phonoscope for November 1899 reported,

Mr. English, well-known in the earlier Edison Phonograph Laboratory work, has taken charge of the new laboratory of the Universal Talking Machine Company on 24th Street, and is manufacturing a full line of flat disc indestructible records, same as the Berliner Gramophone records. The new Company expect to have a full line of records on the market shortly.7

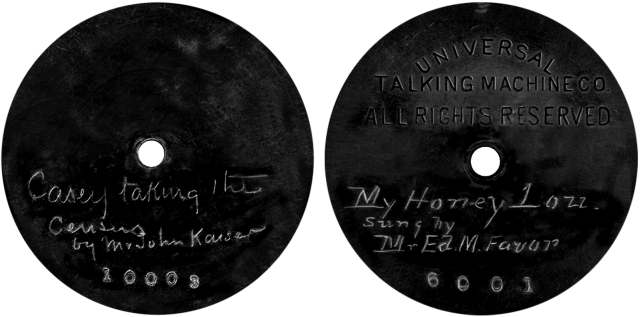

Record manufacturing was contracted to the Burt Company, which had already pressed some discs for Berliner. The earliest original “Zonophone” issues, like their pirated predecessors, were unbranded 7" pressings that probably were produced for only a short time from late 1899 into early 1900. By early 1900, they had been replaced by 7" pressings into which the Universal Talking Machine Company name (but not the Zonophone brand) was embossed, the company’s first attempt at a label design.

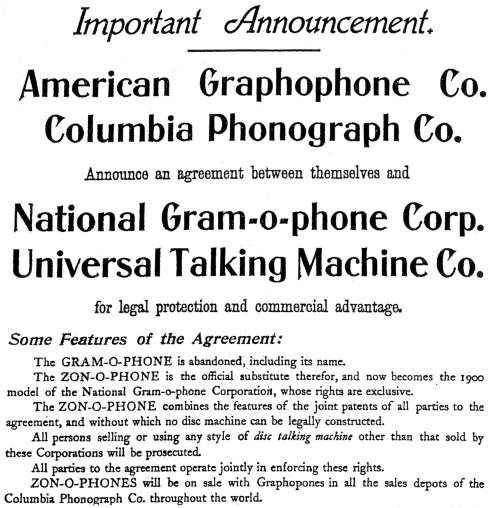

On May 18, 1900, the American Graphophone Company (Columbia) licensed the National Gramophone Corporation and Universal Talking Machine Company, thus providing some patent protection for those companies. Columbia’s motive was simple: It wanted to enter the disc market but had not yet developed its own disc products, so instead it would let its dealers handle the Zonophone line.8

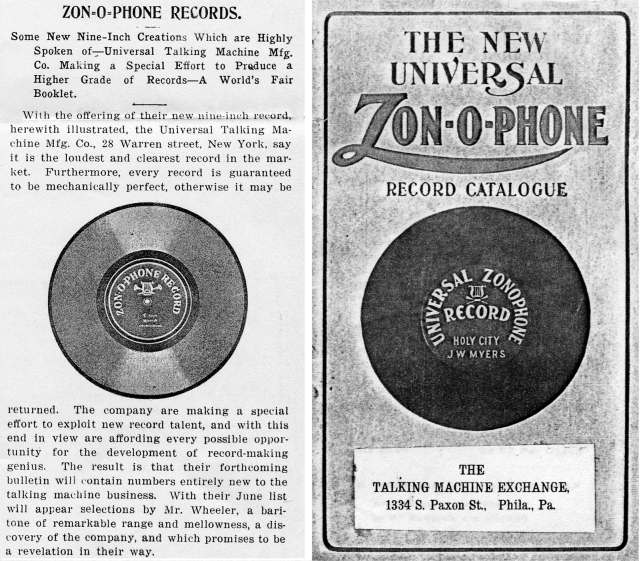

In March 1901, English left Universal Talking Machine for the Globe Record Company, which was beginning to set up its own disc-recording operation. He was immediately sued for breach of contract and disclosure of trade secrets. English’s defense was that he had not discovered or invented anything of significance while employed by Universal, and “now knows no more on the subject than when he first entered plaintiff’s employ.” Universal’s motion was denied, and a temporary injunction against English was vacated. English’s expertise allowed Globe to quickly launch a successful recording operation. Undeterred, Zonophone launched a new line of 9" discs in May 1901, in addition to its 7" offerings. During the same period, Frederick M. Prescott, who had previously exported Zonophone products to Europe, formed the International Zonophone Company in New York. By May 1901 Prescott had opened an office in Berlin, and the first German Zonophone discs were issued in September of that year.

The National Gramophone Company was declared bankrupt on September 6, 1901, with patents and equipment passing to one Edward Innet, as trustee.9 The company was subsequently reorganized as the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company, which was incorporated on December 19, 1901. The new company would be responsible for the manufacturing of Zonophone products, while the Universal Talking Machine Company would remain in operation as sales agent. Louis Valiquet remained, and he assigned a number of important patents to the company.

Columbia began marketing its own disc phonographs and records in October 1901, with the Globe Record Company (having put John English’s expertise to good use) supplying the latter. At that point, Columbia had no further need for Zonophone, which it now viewed as a competitor, and did not offer a license to the new Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company. On March 2, 1902, Columbia attacked the vulnerable new company, charging it with infringement of its crucial Bell-Tainter patent. An injunction was granted on November 25, barring the manufacture and sale of records by the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company.

Within a matter of days, Columbia began threatening legal action against dealers who continued to handle Zonophone products. Violators were ordered to deliver their Zonophone inventory to judicial custody for destruction, with an accounting for damages to follow. In response, Universal Talking Machine offered to pay the legal defense fees of any dealer who was sued,10 but Columbia’s tactics proved effective in driving away most dealers.

By early 1903, with Zonophone products now virtually unsalable, Universal Talking Machine sent a letter to dealers promising that it was “preparing to supply records made by a process not enjoined.”11 No details were offered concerning what that process might be, but a new series of 7" and 9" discs numbered in the 5000s (still bearing embossed labels) was introduced, apparently as an attempt to skirt the injunction. Sales of the new series appear to have been negligible, based on the scarcity of the embossed-label 5000-series discs. It is uncertain whether a catalog was ever issued (none could be found in the course of research for this work), and a large number of issues remain unaccounted for.

Despite its legal and financial problems, Universal announced that it was opening its own pressing plant in April 1903, with George Cheney serving as superintendent. As later events would confirm, it was actually the New York City branch of the Auburn Button Works, which had been trying for several years to break into the record-pressing business. In May, Universal announced the impending arrival of a new line of brown-shellac pressings, which were also the first Zonophone discs to carry paper labels. In a move that has confused more than a few collectors and discographers, the new discs were also numbered in 5000s, but rather than continue the numbering from the point at which the embossed-label issues ended, it was begun over at #5000. Many recordings from the short-lived etched-label 5000 series were reissued in the new paper-label 5000 series, but with different catalog numbers.

In the meantime, events were under way that would finally break the stalemate with Columbia. Universal vice-president Frank. J. Dunham approached the Gramophone & Typewriter Company, Ltd. (Victor’s English sibling) about a possible sale of his company. In April, G & T began formal negotiations for the purchase of the Universal Talking Machine Company, the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company, and the latter’s share in the International Zonophone Company. The initial offer was made through Deutsche Grammophon (G & T’s German affiliate in Berlin), acting as G & T’s agent. After two months of bargaining, an agreement was finally reached to sell the companies to G & T. The sale was settled on June 6, 1903, and the change of ownership became official on August 1.

Once the sale was completed, G & T general manager William Barry Owen approached Victor president Eldridge Johnson with an offer to sell him a controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine and Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing companies. Johnson, although reportedly unenthusiastic about the prospect, realized that the purchase would allow him to control a potentially troublesome competitor. An anonymous recording-industry official told the Music Trade Review, a bit prematurely,

I am reliably informed that a consolidation of certain talking machine interests has already been consummated, namely, that Eldridge Johnson, president of the Victor Talking Machine Co., has acquired a controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Co., though his name does not figure in the deal as yet.12

In late July, Owen set sail for New York, where his activities were closely watched by the press. A reporter who encountered him at the Waldorf-Astoria on August 21 was unable to obtain any information. “As a matter of fact, I haven’t a word to say yet,” Owen told him. “I certainly want to get all the publicity I can when negotiations are completed.”13 When later asked whether Eldridge Johnson was involved in some way, Owen simply responded, “Why not ask Mr. Johnson? He knows.”14

News of the Johnson purchase was leaked to the press on September 12, 1903, before the sale was officially completed. For $135,000, Johnson received G & T’s controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine and Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing companies, as well as exclusive Zonophone sales rights in the United States, U.S. holdings, Mexico, and Cuba. Within several days of the announcement, it was confirmed that G&T would retain control of the Zonophone brand in England and all other areas not covered by covered by the U.S. agreement.15 There, the Zonophone label would serve as a low-priced companion to the more prestigious Gramophone Record, under G&T’s full control.

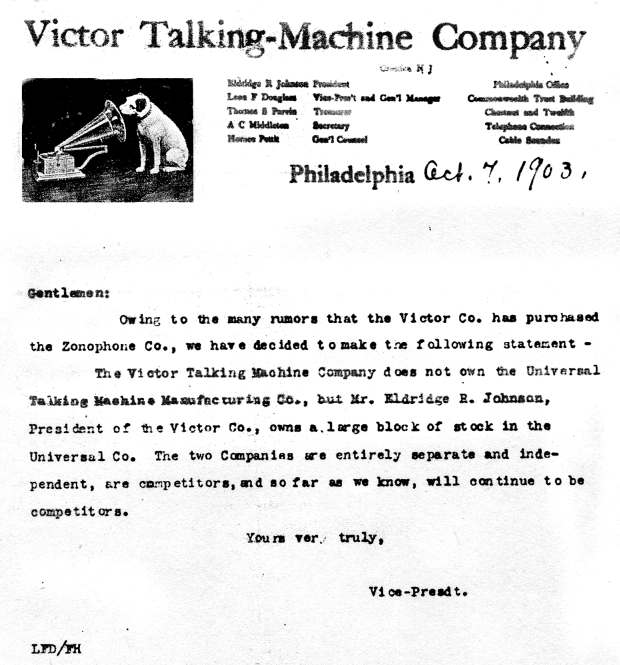

Contrary to a widely repeated misconception, it was Johnson himself — not the Victor Talking Machine Company per se — who purchased Universal Talking Machine. No doubt anticipating further legal attacks on Zonophone by Columbia, Johnson wisely decided to maintain Victor and Universal as separate companies. Victor vice-president Leon Douglass made the situation clear in a letter to the trade dated October 7, 1903:

Owing to the many rumors that the Victor Co. has purchased the Zonophone Co., we have decided to make the following statement: — The Victor Talking Machine Company does not own the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Co., but Mr. Eldridge R. Johnson, President of the Victor Co., owns a large block of stock in the Universal Co. The two companies are entirely separate and independent, are competitors, and, so far as we know, will continue to be competitors.16

The relationship was reiterated in December 1904 by Henry Babson, the recently installed president of the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company, who told the press, “we are now doing business under license from [the Victor Talking Machine] company.17

Johnson had little direct involvement (and reportedly, very little interest) in his newly acquired company, which continued to operate independently for the most part. Its executive staff at the time included Babson, J. A. McNabb (vice-president and general manager), and F. A. Crandall (secretary), none of whom were employees of the Victor Talking Machine Company. Universal Talking Machine’s own studio had been in operation for several years, and it would continue to operate independently for seven more years. Fred Hager, who had been with the company almost from the start, stayed on as musical director, a position he held through March 1906. No indication had been found that Victor personnel at this point were involved in matters regarding artists and repertoire, although that would change in 1910. Except for a few foreign recordings, masters were never exchanged between the two companies.

However, there were subtle signs of new ownership from the start. The company moved into more spacious offices at 28 Warren Street, New York, in February 1904, and the relationship with Auburn Button Works was terminated.18 Instead, pressing was transferred to the Duranoid Company, which was also handling much of Victor’s pressing at that time. The transition was marked by the introduction of a redesigned label and noticeably improved pressings in standard black shellac (replacing Auburn’s notoriously shoddy brown-shellac discs) in April 1904.19 Although the new Zonophone labels did not mention Victor directly, Victor’s patents were added to the reverse-side warning stickers. In November 1904, a new Zonophone machine was announced that incorporated Eldridge Johnson’s tapered tone-arm, a jealously guarded Victor patent.20 Universal originally advertised the new tapered-arm machine at $30, only to discover after completing the first production run that they had priced it too cheaply. On Christmas Eve 1904, the company broke the news that it was raising the price by $5, telling dealers, “It is unnecessary to assure you that it is well worth the difference in price. (It should never have been listed at $30.)” The company later split the difference, pricing them at $27.50.

Johnson was vindicated in his decision to keep the Universal Talking Machine Company at arm’s-length from the Victor Talking Company in late 1903, when composer-conductor Victor Herbert sued Universal. Since early 1900, the company had been marketing Zonophone records attributed to Victor Herbert’s Band; however, Herbert had nothing to do with them. Based upon testimony later presented at trial, it appears that the records were actually made by the 22nd Regiment Band of the New York National Guard, and this apparently was where the Victor Herbert claim (tenuous though it was) originated. Herbert had conducted this band during the 1890s, and had even lent his name to it during his tenure.21 But he left the band in 1898, before Zonophone commenced recording operations, to serve as principal conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony. By the time the first “Victor Herbert’s Band” Zonophones were advertised in 1900, Herbert was touring (but not recording) with a new orchestra that bore his name.

By early 1904, with more than 120 bogus “Herbert’s Band” titles occupying nearly four full catalog pages,22 Herbert finally took action. In January, he applied to Judge Leventritt, of the New York Supreme Court, for an injunction restraining the Universal Talking Machine Company from using his name “for the purposes of trade.” Herbert’s suit was based a recently enacted New York state law that prohibited the use of a person’s name for advertising purposes without prior written consent. Peter B. Olney, Universal’s counsel, opposed the injunction on the grounds that Herbert had long known that his name was being used on Zonophone records, but had sent the company no notice to discontinue the practice.23 His argument was rejected.

Action was delayed while Herbert tended to business in the West,24 but on March 3, 1904, Judge Leventritt ruled in Herbert’s favor and granted an injunction.25 The case went to trial in federal district court in New York on March 9, 1904 (Victor Herbert v. Universal Talking Machine Company). The verdict was in favor of Herbert, on grounds of unfair competition. Universal Talking Machine. In his ruling, the judge affirmed his belief that Herbert “never gave the claimed permission” for Zonophone to use his name, and also expressed his opinion that the matter could be settled “without controversy” pending a full trial.26 It appears that the matter of damages was resolved out of court, while the injunction was allowed to stand.

The injunction left a gaping hole in Zonophone’s catalog that the company scrambled to fill. Some titles were remade during the spring of 1904, employing the house band under Fred Hager’s direction. Many of these remakes bear master numbers in the 2300–2700 range, indicating approximate recording dates of April–June 1904.27

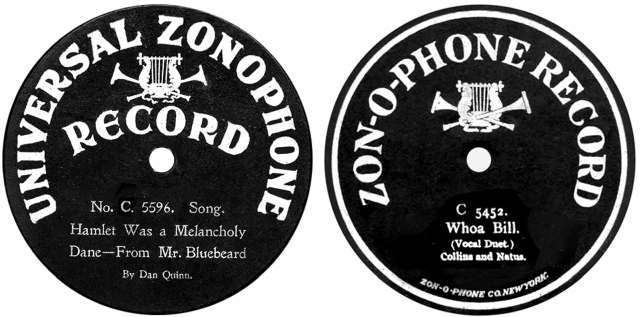

However, remaking all of the “Herbert” titles would be immensely time-consuming (and in the case of the slower-selling titles, probably unprofitable), so the company adopted a second, stopgap strategy. The “Herbert’s Band” recordings were not illegal, per se; only the use of Herbert’s name presented any legal problem. Thus, the company resorted to printing new labels, minus the Herbert credit, for use on the existing “Herbert” recordings while the remake work proceeded. The changeover is easy to pinpoint in the Zonophone sales lists. The “Herbert’s Band” records were still proudly advertised in the February 1904 catalog. But by the time the May 1904 list was published, a new name had appeared that would permanently replace Herbert’s — the Zon-O-Phone Concert Band.28

Relabeling did not entirely solve the problem, however. The relabeled records still had their original spoken announcements crediting Herbert. Bill Bryant and his correspondents identified many specimens bearing the new Zon-O-Phone Concert Band labels, but retaining the incriminating “Herbert” announcements. And so at some point, the company began tooling the announcements off of certain stampers. Pressings from 9" Zonophone mx. 87, for example, are known with and without the announcement, but otherwise are aurally identical.29 By the time that Zonophone 7" and 9" pressings were discontinued in 1905, the last of the “Herbert” recordings had either been dropped from the catalog or been remade by the Zonophone house band.

With the Herbert crisis behind them, Universal announced a new series of ten-inch Zonophone discs in November 1904. They originally retailed for $1 each, the same as Victor’s black-label records but were slashed to 60¢ in late 1905, in line with the price-cutting that was taking place throughout the industry. By then, the company was in the process of phasing out the 7" and 9" lines. Surplus 7" and 9" pressings, pre-dating Johnson’s purchase, remained in the 1905 Zonophone catalogs and were still being advertised at full price as late as December of that year. Eventually, the remaining stock was discounted and liquidated. In 1908, a group of the 7" masters (including some that are not known to have been issued on Zonophone) made their final bow on Sears’ Roebuck’s cut-rate Oxford label.

On March 1, 1905, the receivers for the defunct National Gramophone Corporation auctioned the remaining inventory of pre-Johnson era Zonophone discs. 17 The recording of new 7" masters was quickly discontinued, and the series was phased out over the remainder of the year. Some 7" masters that had not been released on Zonophone, along with many that had, later appeared on Sear Roebuck’s cut-rate Oxford label.

Zonophone’s November 1905 catalog was devoted largely to ten-inch records. Marketing support for the 9" discs had ended a year earlier, and only a handful of new 9" releases appeared after July 1905. In December the company announced that production would be discontinued “in sixty days,” after which the remaining stock would be used only in conjunction with premium plans.30

The remainder of the Zonophone story will be found in Volume I of this work.

Evolution of the American Zonophone Label, 1899 – 1904

Photographs from the George Blacker Collection

(William R. Bryant Papers, Mainspring Press)

Notes

1 National Gramophone Co. “The Vo-co-phone, the Improved Gram-O-Phone” (advertisement). New York Sun (December 19, 1897).

2 Incorporation papers were filed on February 3, 1898, by Orlando J. Hackett, Edward A. Reser, and William Moyse, Jr., all of New York. So far as has been determined, none had any involvement with the operation of the company.

3 “Special Notice.” The Zonophone Record (November–December 1900), p. 1.

4 “Auto-Drive Machine” (advertisement). The Phonoscope (November 1899), p. 20.

5 Cheney, George K. “Talking Machine.” U.S. Patent #640,367 (filed March 3, 1899; granted January 2, 1900).

6 Cheney, George K. “Talking Machine.” U.S. Patent #641,578 (filed April 29, 1899; granted January 16, 1900).

7 “Trade Notes.” The Phonoscope (November 1899), p. 10.

8 “Talking Machine Agreement.” Music Trade Review (June 9, 1900), p. 24.

9 The company remained a legal entity until March 1908, when it was finally voluntarily dissolved. Its last remaining assets, including a large number of foreign patents and its manufacturing formulas, were auctioned in April of that year.

10 “Now After the Dealer.” Music Trade Review (January 3, 1903), pp. 39, 41.

12 “A Talking Machine Consolidation.” Music Trade Review (July 25, 1903), p. 24.

13 “No Positive Statement — The Talking Machine Men Will Not Talk, But Something May Happen Very Soon.” Music Trade Review (August 23, 1903), p. 29.

14 “W. Barry Owen’s Moves.” Music Trade Review (August 8, 1903), p. 35.

15 “News from Germany’s Capitol.” Music Trade Review (February 13, 1904), p. 39.

16 Douglass, Leon F. Letter to the trade (October 7, 1903). William R. Bryant papers, Mainspring Press.

17 “Will Operate Under Victor License.” Music Trade Review (December 17, 1904).

18 Auburn, suddenly left without record-pressing client, soon set up its own recording company in the guise of the International Record Company (Albany, New York), which produced Excelsior records and an extensive line of client labels until being shut down for patent infringement in 1907. Auburn Button survived the shutdown of its recording branch, remaining in business as a plastics-molding firm (with occasional corporate name changes) into the 1960s.

19 “Zonophone Records. Some New Nine-Inch Creations Which Are Highly Spoken Of.” Music Trade Review (May 7, 1904), p. 45.

20 “New Style Zonophone with Tapering Tone Arms—Some of the Claims Made for This Machine.” Music Trade Review (November 19, 1904), p. 111.

21 Gould, Neil. Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life, p. 119. Fordham University Press (2011).

22 “The New Universal Zonophone Records” (February 1904 catalog), pp. 3–6. Copy for this catalog would have been prepared in late 1903 or very early 1904.

23 “Victor Herbert Brings Suit.” Music Trade Review (January 30, 1904), p.40.

24 “That Zonophone Litigation.” Music Trade Review (February 20, 1904), p. 27.

25 “Herbert Gets Injunction.” Music Trade Review (March 9, 1904), p. 4.

26 Victor Herbert v. Universal Talking Machine Company. New York Law Journal (March 3, 1904).

27 Recording-date ranges has been estimated based upon known recording dates taken from test pressings of the period.

28 “Zon-O-Phone Records for May.” Music Trade Review (April 23, 1904), p. 29. Copy for the May list would have been prepared in late March or very early April, after the injunction was upheld. The Zon-O-Phone Concert band was a house ensemble under Fred Hager’s direction.

29 Zonophone C 5057 (mx. 87), 9" paper-label issue. In this case, synchronized aural comparison further confirmed that the recordings are identical, aside from deletion of the announcement. (Bill Bryant papers, Mainspring Press archive.)

30 “Disc Record Prices Reduced.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1905), p. 5. Premium schemes varied greatly, but many involved the customer earning a “free” or deeply discounted phonograph by purchasing a specified number of records.